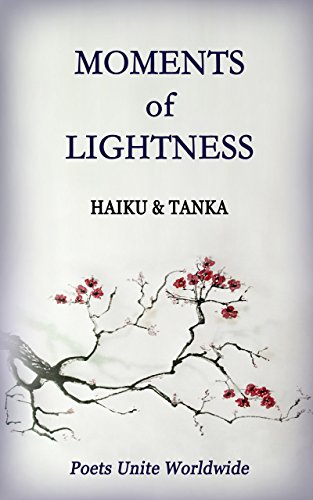

A brief introduction to tanka and haiku poetry

Tanka poetry was born in Japan about 1400 years ago, as a form of ‘waka’ poetry —term meaning “poetry in Japanese”, to distinguish it from ‘kanshi’, that was poetry composed in Chinese by Japanese poets. The term waka originally comprised a number of different forms, most notably tanka, or “short poems”, and ‘chōka’, “long poems”. The first, the most widely composed type of waka, made of five ‘ku’ —phrase(s)— of 5–7–5–7–7 ‘on’

(syllabic units), while chōka encompassed a repetition of 5 and 7 ‘on’

phrases, with the last ‘ku’ containing 7 ‘on’. Although in the Nara period (710–794) and in the very first part of the early Heian period (794–1185), the court favored Chinese-style poetry (the oldest collection of kanshi, the ‘Kaifūsō’, “Fond Recollections of Poetry’, is dated 751; while the ‘Man’yōshū’, “Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves” — the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, compiled in the Nara period, sometime after the year 759— contains 4,207 tanka, 265 chōka, but only 4 kanshi), shortly afterwards waka poetry definitely superseded kanshi, so much so that Emperor Daigo ordered that the waka of ancient poets and their contemporaries were collected in the first imperial waka anthology, in twenty books, with the first six given to seasonal poems (the ‘Kokin Wakashū’ —”Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poems”— usually abbreviated in ‘Kokinshū’, AD 905). Inasmuch as at that time, only two forms of waka were in use, tanka and chōka (with this second hugely diminished in prominence), the term waka became synonymous with tanka; for such a reason this word fell into disuse until Masaoka Shiki, at the end of the 19th century, revived it (along with the haiku form).

‘Utakotoba’, the standard poetic diction established in the Kokinshū, was considered as the very essence of creating a perfect waka, through a sound unit counts of 31 ‘on’, following the pattern 5–7–5 plus 7–7. Although tanka has evolved over the centuries, its ancient form hasn’t changed and remains the original five units of 5–7–5–7–7 ‘on’/syllables.

Through the centuries, the waka/tanka form has been particularly used for poems between lovers and in diaries; more generally, exchanging waka instead of letters in prose has been a widespread custom, since it is a lyric poem that, through its own flow and rhythm, can express the deepest feelings, emotions and thoughts —it is a kind of ‘painting with words’, that uses references to the natural world as well as to the inner feelings of our everyday life.

From waka, over time, a number of poetry genres developed, such as ‘renga’ (collaborative linked verse). As momentum and popular interest shifted to the renga form —in the Muromachi period (1336–1573)— waka was left to the Imperial court, and all commoners were excluded from the highest levels of waka training. Then, during the Edo period (1603–1868), renga poets were able to express broader humor and wit, through a simplified form of renga, where the use of commonly spoken words was allowed: the new style was called ‘haikai no renga’*, or just ‘haikai’ (*comical linked verse, also called ‘renku’). What was traditionally referred to as ‘hokku’, later called haiku, is the opening stanza, 5–7–5 ‘on’, of a renga/haikai —indeed, the first document to record the word ‘haiku’ is thought to be Hattori Sadakiyo’s ‘Obaeshu’, (1663): it was used as an abbreviated form of “haikai-no-ku” (a verse of haikai).

In the second half of 1600, Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), firmly committed to the cause of making haikai the equal of waka and renga, elevated this genre and gave it a new popularity. While waka and renga had belonged to the aristocratic world of court poetry and samurai culture, haikai became the genre of choice for commoners. All of the best haikai masters, used mainly the genre to describe nature and human events directly related to it, and stressed on the great significance of the opening stanza —hokku—, to give poetic relevance to such versification.

Hokku, removed from the context of renga and haikai, eventually became the stand-alone 17 ‘on’ (5–7–5) haiku poetry form; Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), then gave the term ‘haiku’ a special role, so to make it a genre of modern literature in its own right.

By Fabrizio Frosini